The Life of Agnes Pelton

Agnes Pelton (1881–1961) was a visionary painter who sought the meeting point between the visible and the unseen.

Painting, for Agnes was a form of communion. Her paintings emerged from a meditative discipline, a practice of stillness through which she transformed contemplation into form.

Art was both revelation and refuge, a language through which she reached toward what she called “a higher consciousness within the universe.” Born in Germany to American parents, Pelton spent her early years in Europe. After her father’s death from a morphine overdose when she was nine, Pelton and her widowed mother returned from Europe to Brooklyn, where they lived with her maternal grandmother. To support the family, Florence Pelton ran a small art and music studio from their home. Life was modest but steady, shaped by quiet endurance and her mother’s unwavering resilience, a formative environment that nurtured young Agnes’s inward nature and early imagination.

She studied art in both the United States and Europe, developing a foundation that bridged tradition and imagination. Her early works included portraits of Pueblo Native Americans, desert landscapes, and still lifes. Over time, her art evolved through three distinct phases: the early “Imaginative Paintings,” her depictions of the people and terrain of the American Southwest, and finally, the luminous abstractions that expressed her deepest spiritual beliefs. That search for transcendence unfolded not only in her paintings, but in the life she quietly shaped around them.

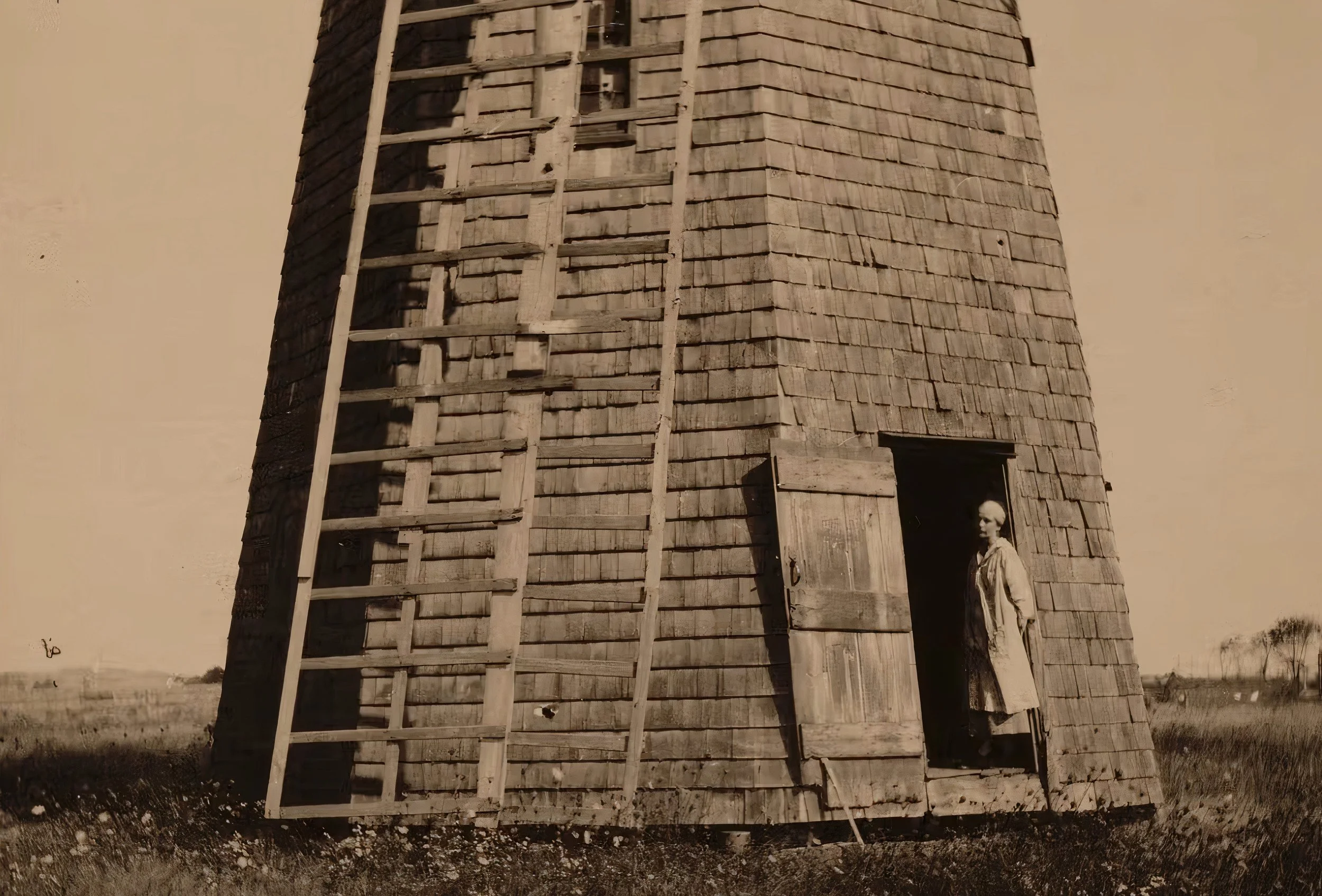

A portrait of Agnes Pelton. By Photographer Alice Boughton. 20th Century

Pelton drew from both classical training and New York City’s growing energy of experimentation.

Agnes studied at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, graduating in 1900 alongside fellow modernist Max Weber. During this time, she worked closely with Arthur Wesley Dow, whose teaching blended Japanese aesthetics with the modernist harmony of light, form, and imagination.

Dow’s influence was central to Pelton’s development of abstractions grounded in spiritual values, and his ideas also shaped artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe. He encouraged his students to look beyond realism and to see structure, color, and space as expressions of inner life.

Pelton studied in Italy in 1910 and 1911, taking life drawing lessons and studying Italian painters at the British Academy in Rome. She also studied with Hamilton Easter Field, another of her Pratt instructors, and took summer classes with William Langson Lathrop. These experiences refined her understanding of composition, deepened her sensitivity to tone and light, and strengthened her belief that art could express both emotion and spirit.

At the 1913 Armory Show, Pelton exhibited Vine Wood and Stone Age. In Vine Wood, she shaped a dreamlike world of layered greens where a lone figure blends into the foliage as monkeys move above—a vision of calm and unease where self and nature become one. This material is in the public domain in the United States because it was published or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office before January 1, 1930.

Pelton drew from both classical training and New York City’s growing energy of experimentation.

Her work was exhibited in Ogunquit, Maine, at Field’s studio in 1912. Based on her work shown there, Walt Kuhn invited her to participate in the 1913 Armory Show, where two of her paintings, Stone Age and Vine Wood, were exhibited.

The works she called her “Imaginative Paintings,” influenced by Arthur B. Davies, explored the effects of natural light and the inner atmosphere of landscape. She created these poetic, light-filled canvases between 1911 and 1917. Her participation in the 1913 Armory Show placed her among the early voices of modernism, grounding her later spiritual vision in the discipline of craft and the evolving language of abstraction.

After her mother’s death in 1920, Pelton sought solitude at the Hayground Windmill on Long Island. In that quiet refuge, she turned inward, finding in isolation a path toward spiritual clarity. The desert would call to her a decade later.

“The vibration of this light, the spaciousness of these skies enthralled me. I knew there was a spirit in nature as in everything else, but here in the desert it was an especially bright spirit.”

— Agnes Pelton

Smoke Trees in a Draw, ca. 1950, oil on canvas, 25 × 31 1/2 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Western Art Council, Mary James Memorial Fund, 2008, 31-2008.

Pelton’s love affair with the desert skies and their quiet, mystical presence began after a visit to Mabel Dodge Luhan in Taos, New Mexico. Mabel, a writer and lifelong patron of the arts, had helped organize the landmark 1913 Armory Show that introduced modernism to America. Later, she became a guiding force of the Taos art colony, drawing artists and writers such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Ansel Adams, and Willa Cather to her home. In that luminous world of open sky and creative exchange, Pelton discovered the desert’s spiritual power—a landscape that would forever shape her vision and her art.

Before finding her home in the desert, Pelton traveled widely—to Hawaii, Beirut, Syria, Georgia, and throughout California. In Hawaii, during 1923 and 1924, she painted portraits and still lifes that reflected both her technical mastery and her growing sensitivity to atmosphere. She exhibited her work in New York at the Argent Galleries and at the Museum of New Mexico. By that time, she had already participated in twenty group exhibitions and fourteen solo shows.

Photograph of Mabel Dodge Luhan and her husband, Tony Luhan, taken by Agnes Pelton during one of their visits to her Cathedral City home.

A Life Shaped by Light, Tranquility, and Spiritual Illumination Beneath Desert Skies.

Pelton arrived in Cathedral City, California, in late 1931, intending only a short stay. The quiet expanse of the desert soon captured her, and she made it her home for nearly thirty years. Beneath those vast skies, she found both solitude and inspiration to pursue her spiritual abstractions. To sustain herself, she painted western landscapes and commissioned portraits—each one a means to support the deeper calling that defined her life’s work and legacy.

On March 2, 1936—her father’s birthday, Pelton made a down payment on Lot #228 in the Cathedral City Development. She noted with quiet wonder how each stage of the process, from the bank loan to the construction of her home, aligned with a series of astrological signs she had been following. Two years later, in 1938, Mabel Dodge Luhan, her husband Tony, and the painter Dorothy Brett visited Pelton in Cathedral City, linking her desert retreat once again to the creative circle that had first drawn her west.

Friendship in Focus:

Agnes Pelton & Alice Boughton

As a trusted friend and fellow artist, Alice Boughton documented Pelton at the threshold of her creative awakening.

In the mid-1910s, painter Agnes Pelton developed a creative and personal connection with photographer Alice Boughton, resulting in several photographic sessions that captured Pelton at pivotal moments in her artistic life. Although the exact number of sessions is uncertain, archival prints indicate multiple sittings over a span of years.

This visual collaboration offers a rare and intimate glimpse into the formation of Pelton’s artistic identity, preserved through Boughton’s lens.